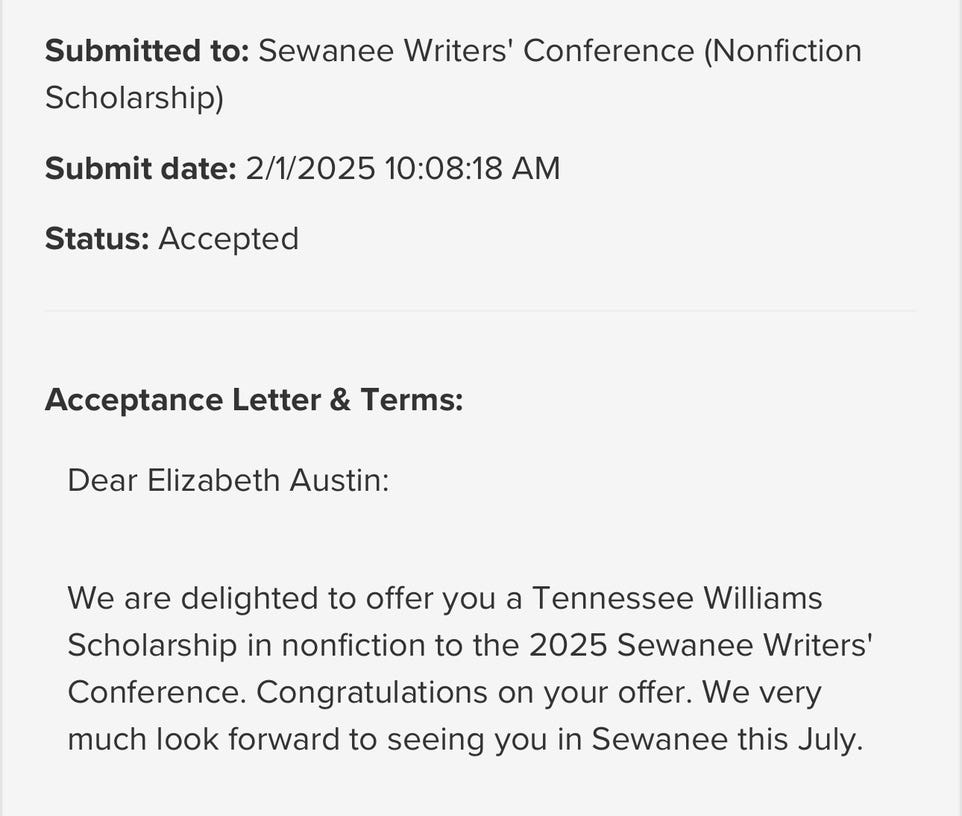

First, some good news: in the middle of a day filled with appointments and errands for the kids, in a brief moment between taking Jack for an eye exam and stopping to pick up European plug adapters, I tapped open my Gmail icon and saw “Sewanee Writers’ Conference Admission Decision” at the top of my inbox. I was caught off guard— I try to put conference applications out of my mind so they don’t drive up my anxiety— and I opened the email before I could fret over what it might say.

Poor Jack was in the car with me and had to endure my top-volume “OH MY GOD HOLY SHIT” and the delighted (but still way too loud) voice messages I sent to two of my close friends from a Best Buy parking lot.

Melissa Febos is one of the nonfiction instructors this summer, and I applied specifically with the hopes of working with her, or at least getting to say hi. I remember putting my application together in February, taking one last look at her name in the instructor list, hitting “Submit,” and thinking, there’s no fucking way.

But there is a way! I got in and I’m going! I’ve been through all 17 pages of the overview document, I submitted my workshop materials, filled out my preferences forms, I have my travel plans sorted, and I’m piecing together care for the kids.

Most important, I’m letting myself feel this win.

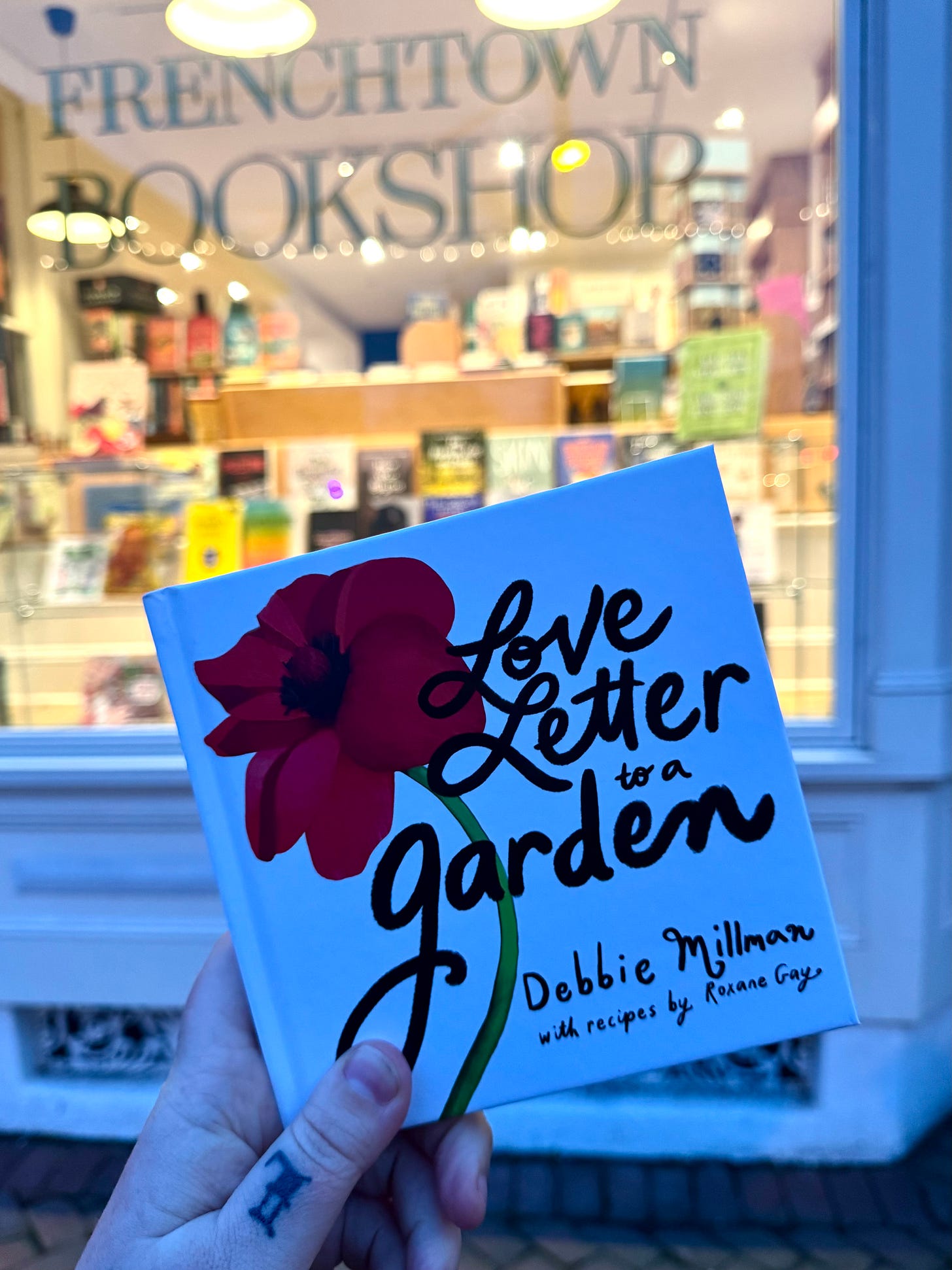

Last week I attended a book event for Debbie Millman’s (incredible, absorbing, magical!) Love Letter to a Garden at the Frenchtown Bookshop. Carolyn tagged along— she loves cooking and gardening, not to mention beautiful illustration. I’d told her about the book and the event knowing she’d want to have her own copy and maybe get it signed. She’s enthralled each time she gets to meet a real live writer! (who’s going to tell her?)

At the event, a woman I hadn’t seen in a while came up to chat. We talked for a bit, nothing deep, and she mentioned she’d seen Carolyn and me last year at Suleika Jaouad’s and Anne Francey’s art opening. She asked how Carolyn had responded to Suleika’s paintings in particular, and I told her about how Carolyn talked about the paintings for weeks after the opening, how she asked me how she could buy “the elephant one.”

I remembered watching Carolyn move from room to room through the crowd. She’d paused in front of each painting, taking in images of illness and survival that she knows intimately.

How is she doing now? the woman asked, and my mouth formed the words before my brain could intervene.

She’s doing great, I said, gesturing to the top of Carolyn’s head just visible over the New Releases bookshelf. Thriving! She’s in seventh grade, has lots of friends, just a totally normal teenager!

It was a reflex, the way you say fine, thanks! when someone asks how you are, even if your house is on fire and the dog ran away. After the words left my mouth, my stomach knotted and my skin felt tight.

I keep that phrase— she’s thriving!— in my back pocket like a business card, ready to hand out any time someone asks how Carolyn is doing. It’s efficient, it’s comforting to the person I’m saying it to, and it’s a simple answer to an unanswerable question.

What might I say if I told the truth? That cancer doesn’t end with remission. That the trauma of it is a slow leak. That she struggles with chronic pain and neuropathy every day, fatigue is her baseline, and school is a daily tightrope walk. Forming new friendships has been a struggle because she lost years of developmental milestones to a hospital bed and a fluid drip.

How do I tell a near-stranger that there’s a psychic scarring that never shows up on scans but lives in all of us, under our skin and around our organs and in the backs of our minds, and we have to eat and breathe and live around it all the time? I don’t know what to say to people who ask how we’re doing so I say we’re doing great! and each time I say it I feel all of my wounds start to ooze.

Carolyn is in seventh grade. She has made some friends, but she still gets anxious in groups of people and looks to me for an anchor. She spends more time hanging out with her mom than other kids her age, and her social battery is about half that of her friends’.

Her knees bother her the way mine will when I’m 85. She struggles to walk long distances. She struggles to run. She counts the bruises that accumulate on her legs and asks me which ones mean her cancer is coming back.

I don’t know how to look into a near-stranger’s hopeful face and say, “Actually, she’s still recovering. She’ll probably always be recovering.”

More than that, I don’t want to ruin their day. It feels crass, somehow, to tell the truth, like I’m weaponizing sadness. I feel compelled to deliver a narrative they can digest, the version of the story that lets them unclench their shoulders, smooth down their fears, and go back to their glass of wine or their drive home along the river.

Sometimes I feel irrationally angry. Not at them and not at the question of how Carolyn is doing— it isn’t their fault that I feel obligated to comfort them— but at the absurdity of it all. My kid had cancer. How could anyone think she’d ever be entirely okay again? How could anyone believe she’d be great, thriving even?

When Carolyn was in treatment, she was bald with a feeding tube taped to her face. No questions about how we were doing then.

Now our wounds are invisible, and the expectations of healing are so high. The times I do tell people something close to the truth— that we’ll never completely return to our pre-cancer life— I see a shade drop behind their eyes. They think that we could if we wanted to, that it’s a matter of perspective and willpower. I don’t know how to tell people that wanting is not enough.

No one hands you a manual for how to catch a kid up after giving the last years of their childhood over to cancer. There isn’t a guidebook for how to process the aftermath or what to say to people when they ask how she’s doing, how you’re doing, their faces eager and expectant.

I don’t want to be the person who leaves a bad taste in well-intentioned peoples’ mouths by reminding them that sometimes survival doesn’t look like a triumph. I don’t want to always be dragging everyone back into the murk.

Carolyn’s face appeared around the bookshelf’s end, her eyes wide and wandering until they caught mine. She grinned, the baby blue bands on her braces peeking through her parted lips. She clutched her book to her chest, ready to get in line to have it signed.

She looks great, the woman said, and I nodded because she does. It wasn’t a placation. I didn’t feel pulled to undercut or qualify it. I was awash in the relief of watching my daughter walk around a bookstore on legs like pulled taffy, her knobby knees poking through the intentional rips in her jeans.

I love watching her take up space in the world.

I knew it was an odd thing to say, but it landed somewhere in the middle of this woman’s need for a neat ending and my ragged hanging threads. Close enough.

I’ve learned that often, people don’t want truth— they want a soundbite. They want the tidy ending to a story that scared them. She had cancer is the horror. She’s thriving is the denouement. We can all go home now.

I can’t leave the story so easily. I’m still living in the after, sorting through the rubble of what cancer cost Carolyn and what it took from me, and in the meantime I’m making peace with the fact that sometimes a lie is shorthand for a truth that’s still unfolding.

Such beautiful and true words, Elizabeth.

This is such an important message for anyone who hasn't gone through this experience.

I often decide in a split second on how to answer someone when they ask how many children I have--assuming that I do have children.

If I feel a connection or think I'll interact with them again, I'll say two--an earth son and a spirit son.

I let their discomfort settle but then always end up saying something to make them feel better, so I get that.

😌

Best of luck with your conference and many joyful moments with your daughter. ❤️

This is so beautiful, Elizabeth--and so is Carolyn, and so are you. Also, congratulations on Sewanee!!